A significant shift in culture occurred in France and elsewhere at the beginning of the 18th century, known as the Enlightenment, which valued reason over authority. In France, the sphere of influence for art, culture and fashion shifted from Versailles to Paris, where the educated bourgeoisie class gained influence and power in salons and cafés. The new fashions introduced therefore had a greater impact on society, affecting not only royalty and aristocrats, but also middle and even lower classes. Ironically, the single most important figure to establish Rococo fashions was Louis XV’s mistress Madame Pompadour. She adored pastel colors and the light, happy style which came to be known as Rococo, and subsequently light stripe and floral patterns became popular. Towards the end of the period, Marie Antoinette became the leader of French fashion, as did her dressmaker Rose Bertin. Extreme extravagance was her trademark, which ended up majorly fanning the flames of the French Revolution.

Fashion designers gained even more influence during this era, as people scrambled to be clothed in the latest styles. Fashion magazines emerged during this era, originally aimed at intelligent readers, but quickly capturing the attention of lower classes with their colorful illustrations and up-to-date fashion news. Even though the fashion industry was ruined temporarily in France during the Revolution, it flourished in other European countries, especially England.

During this period, a new silhouette for women was developing. Panniers, or wide hoops worn under the skirt that extended sideways, became a staple. Extremely wide panniers were worn to formal occasions, while smaller ones were worn in everyday settings. Waists were tightly constricted by corsets, provided contrasts to the wide skirts. Plunging necklines also became common. Skirts usually opened at the front, displaying an underskirt or petticoat. Pagoda sleeves arose about halfway through the 18th century, which were tight from shoulder to elbow and ended with flared lace and ribbons. There were a few main types of dresses worn during this period. The Watteau gown had a loose back which became part of the full skirt and a tight bodice. The robe à la française a

During this period, a new silhouette for women was developing. Panniers, or wide hoops worn under the skirt that extended sideways, became a staple. Extremely wide panniers were worn to formal occasions, while smaller ones were worn in everyday settings. Waists were tightly constricted by corsets, provided contrasts to the wide skirts. Plunging necklines also became common. Skirts usually opened at the front, displaying an underskirt or petticoat. Pagoda sleeves arose about halfway through the 18th century, which were tight from shoulder to elbow and ended with flared lace and ribbons. There were a few main types of dresses worn during this period. The Watteau gown had a loose back which became part of the full skirt and a tight bodice. The robe à la française a lso had a tight bodice with a low-cut square neckline, usually with large ribbon bows down the front, wide panniers, and was lavishly trimmed with all manner of lace, ribbon, and flowers. The robe à l’anglais featured a snug bodice with a full skirt worn without panniers, usually cut a bit longer in the back to form a small train, and often some type of lace kerchief was worn around the neckline. These gowns were often worn with short, wide-lapeled jackets modeled after men’s redingotes. Marie Antoinette introduced the chemise à la reine (pictured right), a loose white gown with a colorful silk sash around the waist. This was considered shocking for women at first, as no corset was worn and the natural figure was apparent. However, women seized upon this style, using it as a symbol of their increased liberation.

lso had a tight bodice with a low-cut square neckline, usually with large ribbon bows down the front, wide panniers, and was lavishly trimmed with all manner of lace, ribbon, and flowers. The robe à l’anglais featured a snug bodice with a full skirt worn without panniers, usually cut a bit longer in the back to form a small train, and often some type of lace kerchief was worn around the neckline. These gowns were often worn with short, wide-lapeled jackets modeled after men’s redingotes. Marie Antoinette introduced the chemise à la reine (pictured right), a loose white gown with a colorful silk sash around the waist. This was considered shocking for women at first, as no corset was worn and the natural figure was apparent. However, women seized upon this style, using it as a symbol of their increased liberation.

Women’s heels became much daintier with slimmer heels and pretty decorations. At the beginning of the period, women wore their hair tight to the head, sometimes powdered or topped with lace kerchiefs, a stark contrast to their wide panniers. However, hair progressively was worn higher and higher until wigs were required. These towering tresses were elaborately curled and adorned with feathers, flowers, miniature sculptures and figures. Hair was powdered with wheat meal and flour, which caused outrage among lower classes as the price of bread became dangerously high.

Men generally wore different variations of the habit à la française: a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. The waistcoat was the most decorative piece, usually lavishly embroidered or displaying patterned fabrics. Lace jabots were still worn tied around the neck. Breeches usually stopped at the knee, with white stockings worn underneath and heeled shoes, which usually had large square buckles. Coats were worn closer to the body and were not as skirt-like as during the Baroque era. They were also worn more open to showcase the elaborate waistcoats. Tricorne hats became popular during this period, often edged with braid and decorated with ostrich feathers. Wigs were usually worn by men, preferably white. The cadogan style of men’s hair developed and became popular during th

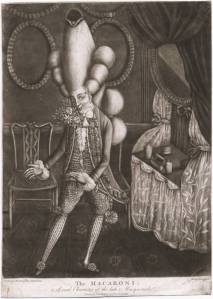

Men generally wore different variations of the habit à la française: a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. The waistcoat was the most decorative piece, usually lavishly embroidered or displaying patterned fabrics. Lace jabots were still worn tied around the neck. Breeches usually stopped at the knee, with white stockings worn underneath and heeled shoes, which usually had large square buckles. Coats were worn closer to the body and were not as skirt-like as during the Baroque era. They were also worn more open to showcase the elaborate waistcoats. Tricorne hats became popular during this period, often edged with braid and decorated with ostrich feathers. Wigs were usually worn by men, preferably white. The cadogan style of men’s hair developed and became popular during th e period, with horizontal rolls of hair over the ears. French elites and aristocrats wore particularly lavish clothing and were often referred to as “Macaronis,” as pictured in the caricature on the right. The lower class loathed their open show of wealth when they themselves dressed in little more than rags.

e period, with horizontal rolls of hair over the ears. French elites and aristocrats wore particularly lavish clothing and were often referred to as “Macaronis,” as pictured in the caricature on the right. The lower class loathed their open show of wealth when they themselves dressed in little more than rags.

Fashion played a large role in the French Revolution. Revolutionaries characterized themselves by patriotically wearing the tricolor—red, white, and blue—on rosettes, skirts, breeches, etc. Since most of the rebellion was accomplished by the lower class, they called themselves sans-culottes, or “without breeches,” as they wore ankle-length trousers of the working class. This caused knee breeches to become extremely unpopular and even dangerous to wear in France. Clothing became a matter of life or death; riots and murders could be caused simply because someone was not wearing a tricolor rosette and people wearing extravagant gowns or suits were accused of being aristocrats.

The Rococo era was defined by seemingly contrasting aspects: extravagance and a quest for simplicity, light colors and heavy materials, aristocrats and the bourgeoisie. This culmination produced a very diverse era in fashion like none ever before. Although this movement was largely ended with the French Revolution, its ideas and main aspects strongly affected future fashions for decades.

Women. Women’s clothing became much less restricting. Flexible stays replaced hard, tight-fitting corsets. Flowing lace collars replaced stiff ruffs. Large farthingales were abandoned and skirts were merely layered or padded at the hips to produce a full, flowing look. Usually two skirts were worn, the overskirt (manteau) open at the front and usually forming a train or bustle at the back, and an underskirt. Decorative aprons became popular with the middle classes. The plunging neckline called the décolletage became common, often accompanied with wide lace collars. Waistlines were also high during the first part of the period, though long, pointed bodices and stiff stomachers came back during the latter half of the period. Sleeves were large, gathered at the wrist or elbow and often with turned-back lace cuffs. They progressively became more and more ruffled and segmented as the period progressed. Solid-colored silks and brocades were used more often than patterned fabrics, and usually decorations consisted only of lace, tied or rosetted ribbons, limited embroidery, and simple pearl jewelry.

Women. Women’s clothing became much less restricting. Flexible stays replaced hard, tight-fitting corsets. Flowing lace collars replaced stiff ruffs. Large farthingales were abandoned and skirts were merely layered or padded at the hips to produce a full, flowing look. Usually two skirts were worn, the overskirt (manteau) open at the front and usually forming a train or bustle at the back, and an underskirt. Decorative aprons became popular with the middle classes. The plunging neckline called the décolletage became common, often accompanied with wide lace collars. Waistlines were also high during the first part of the period, though long, pointed bodices and stiff stomachers came back during the latter half of the period. Sleeves were large, gathered at the wrist or elbow and often with turned-back lace cuffs. They progressively became more and more ruffled and segmented as the period progressed. Solid-colored silks and brocades were used more often than patterned fabrics, and usually decorations consisted only of lace, tied or rosetted ribbons, limited embroidery, and simple pearl jewelry.